Researchers have uncovered the key to the structural stability of microscopic particles that carry materials from one cell to another via blood vessels and other body fluids: unique proteins that maintain their membranes while navigating fluctuating electrical impulses in various biological settings.

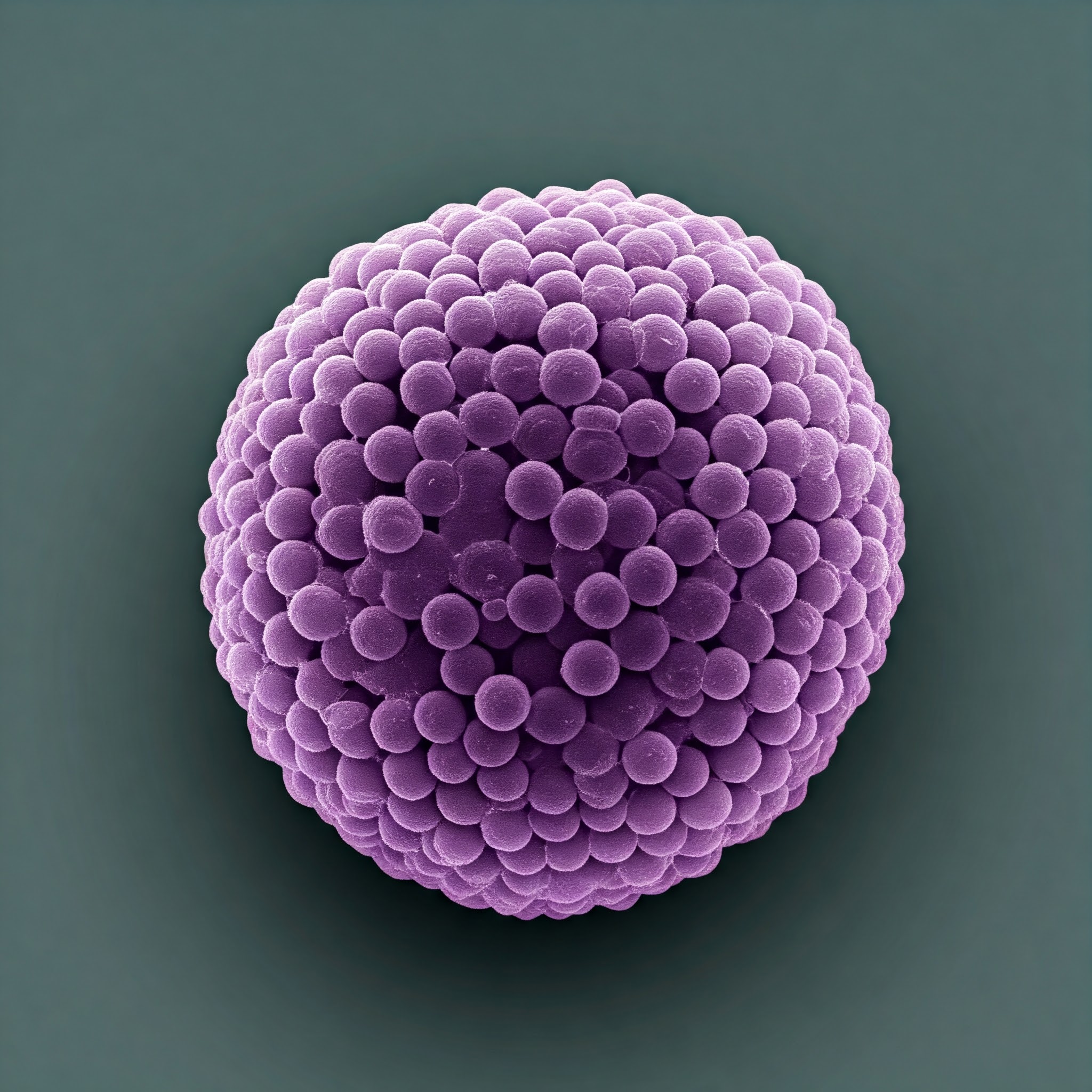

These particles are referred to as extracellular vesicles, and they are thought to be appealing drug delivery systems. However, the full picture of how they operate has not yet been available to researchers.

An ion channel, a protein that creates a passageway for electrical charges to flow through the protective outer membrane, is present in these vesicles, according to a recent study conducted by a group of medical researchers at The Ohio State University. This is a necessary step to maintain the stability of the contents and conditions inside the vesicles.

Additionally, studies on animals demonstrated that the ion channel affects the cargo, indicating that the protein is crucial for both the construction and function of extracellular vesicles (EVs). In mice with sick hearts, researchers examined the impact of RNA molecules administered by EVs with and without the membrane protein. The damage to the heart could only be repaired by chemicals delivered by EVs with ion channels.

We have not only discovered ion channels in these vesicles. We have recorded functional ion channels for the first time ever,

From forming a simple fundamental hypothesis that these vesicles should have ion channels all the way to showing that these vesicles will contain different cargo that can either protect or harm your cells – in this case, the heart – we have told the whole story.

Harpreet Singh

Their findings were published in the journal Nature Communications.

Extracellular vesicles transport proteins and other substances from donor cells to destination cells to change physiological and biological reactions. The particles have been connected to immunological responses, viral infectiousness, cardiovascular illness, cancer, and neurological problems in addition to promoting cellular communication and preserving cellular homeostasis.

Singh’s expertise in ion channel research led him to hypothesize that EVs need ion channels in order to safely move chemicals from the inside of cells to the extracellular space and back again. Otherwise, when the positive and negative electrical charges of ions fluctuate in those different settings, their membranes would be vulnerable to bursting, which would be brought on by a surge of water that is induced by osmotic stress or shock.

We know from our experience and from all this great work done in the last hundred years that ion channels are really, really important to maintain any structure which has a membrane.

Harpreet Singh

For instance, consider potassium, an electrolyte. Although it is the most prevalent positively charged ion within cells, the extracellular environment has a 30-fold lower concentration of it.

Suddenly an extracellular vesicle is coming from a huge potassium concentration to a low potassium concentration. What is going to happen if you can’t maintain ionic balance? You are going to feel the osmotic shock.

Harpreet Singh

Khan, who is also the head of basic and translational research in the Department of Emergency Medicine, supplied the researchers with isolated mice EVs for this study. Khan’s group specializes in using stem-cell therapy to mend injured heart muscle.

The researchers developed a method they named near-field electrophysiology to measure currents in the EV membranes since these particles are so tiny. The technique demonstrated the existence of a large-conductance potassium channel (BKCa) that is triggered by calcium.

They then separated EVs from normal mice and knockout mice that lacked the gene for the BK potassium channel. They discovered that the cargo in the knockout mice’s EVs differed significantly in size and quantity, indicating that the BKCa channel serves a functional purpose.

According to Khan, the cargo in the typical mouse vesicles contained a number of short RNA segments that control gene activation and are known to aid in defending the heart against oxidative stress. A distinct collection of these segments, known as microRNAs, was found in EVs from mice deficient in the BK channel gene.

This discovery prompted Khan’s group to conduct animal tests in which mice with cardiac diseases were given EVs from both normal and BK gene-deficient animals.

EVs from the wild-type animals protected the heart,

EVs that came out of the knockout mice could not protect the heart properly and, in fact, made things worse. Bad microRNAs were enriched in the vesicles that don’t have the channel.

Is the cargo different because of different packaging, or is it because the vesicles without the channels are not surviving? That is an open question, and we are trying to address that.

Harpreet Singh

Another major outstanding topic is discovering proteins called transporters that allow vesicles to maintain ionic equilibrium when they return from the external environment to a cell with a high potassium content.

Singh stated that this finding has the potential to improve the development of extracellular vesicles as therapies in addition to boosting fundamental information about them.

Also Read: Researchers Uncovered the 3D Structure of Ribozyme

People talk about loading these vesicles with charged molecules – whether it’s a drug, RNA proteins, or something else. If you’re loading them with charged molecules and you’re not managing ion homeostasis, you will have some sort of consequences,

That’s our big point, that if you are bioengineering EVs, you have to have the right combination of ion channels and transporters.

Harpreet Singh

Source: Ohio State News

Journal Reference: Sanghvi, Shridhar, et al. “Functional Large-conductance Calcium and Voltage-gated Potassium Channels in Extracellular Vesicles Act As Gatekeepers of Structural and Functional Integrity.” Nature Communications, vol. 16, no. 1, 2025, pp. 1-11, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55379-4.

Last Modified: