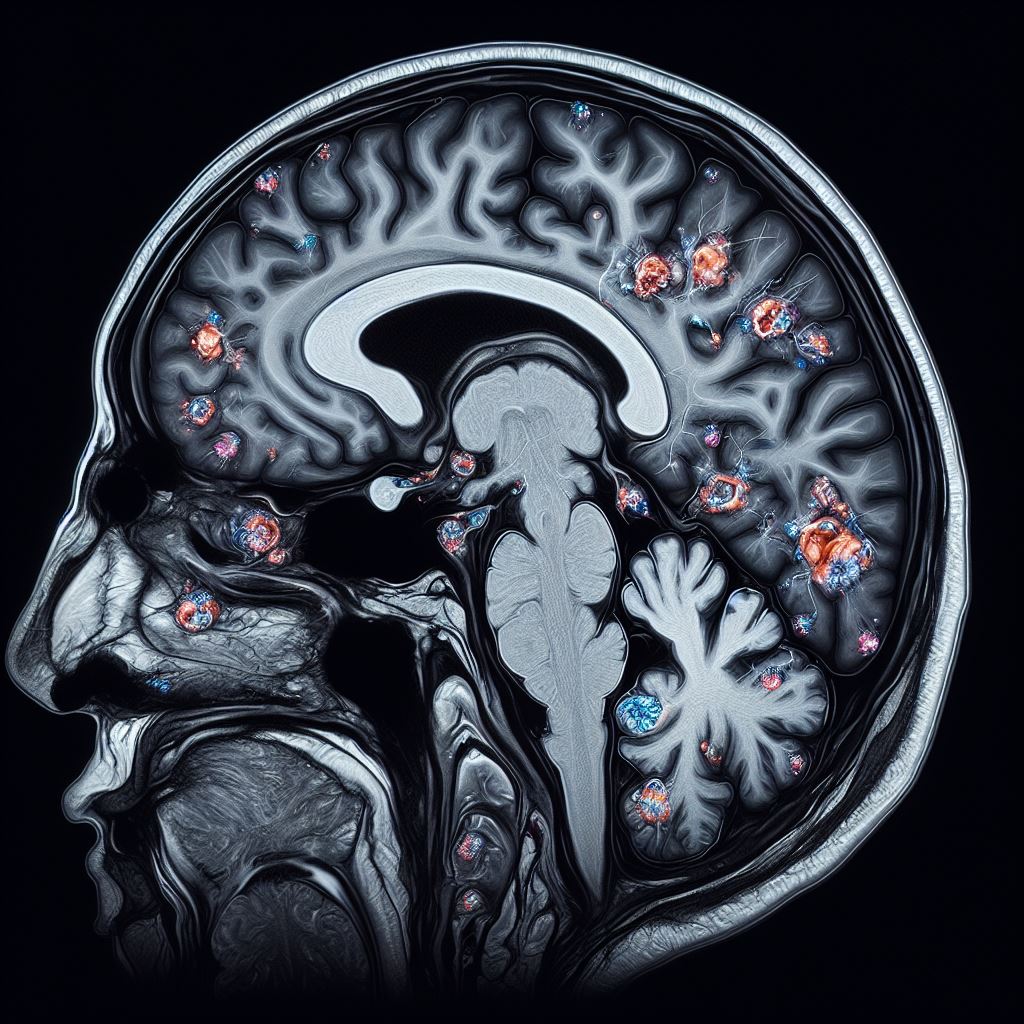

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have shown that a drug used to treat epilepsy in children also inhibits the growth and development of brain tumors in two mouse models of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). Due to a genetic disorder called NF1, tumours can grow on any nerve in the body, including the optic nerves that carry information from the eyes to the brain.

The results set the stage for a clinical trial to see if lamotrigine, a medication, may stop or slow brain tumours in kids with NF1. The study may be found online in the Neuro-Oncology journal.

Based on these data, the Neurofibromatosis Clinical Trials Consortium is considering launching a first-of-its-kind prevention trial.

The plan is to enroll kids without symptoms, treat them for a limited time, and then see whether the number of children who develop tumors that require treatment goes down.

This is a novel idea, so we took it to an NF1 patient focus group,

This is exactly what we’re looking for.’ A short-term treatment with a drug that has been used safely for 30 years was acceptable to them if it reduced the chance their children would develop tumors and need chemotherapy that might have all kinds of side effects.

David H. Gutmann, MD, PhD, the Donald O. Schnuck Family Professor of Neurology and the director of Washington University’s Neurofibromatosis Center.

Optic gliomas, the most dangerous tumours that NF1 carriers receive, are tumours that impact the optic nerve. The age range for these tumours usually extends from 3 to 7. Although they seldom result in death, they can cause up to a third of patients to lose their vision in addition to other symptoms including early puberty. Conventional chemotherapy for optic gliomas can harm children’s growing brains, leading to behavioural and cognitive issues, and is only mediocrely successful at stopping future eyesight loss.

In a prior investigation, lamotrigine inhibited the formation of ocular gliomas in NF1 mice by reducing neuronal hyperactivity, as demonstrated by Gutmann and Corina Anastasaki, PhD, an assistant professor of neurology and the lead author of the current work. Their research caught the attention of the Neurofibromatosis Clinical Study Consortium, but they insisted on further proof before they would consider initiating a clinical study. Members of the consortium requested that Gutmann and Anastasaki elucidate the relationship among Nf1 mutation, neuronal excitability, and optic gliomas; evaluate the efficacy of lamotrigine at doses that have previously been shown to be safe in paediatric epilepsy patients; and carry out these investigations in multiple strains of NF1 mice.

NF1 is a very varied illness in humans. It can be caused by any one of thousands of possible NF1 gene mutations, each of which has the potential to generate a unique set of health issues. Lamotrigine’s potential to function in humans independently of the underlying mutation was assessed by repeating studies in several strains of mice.

In addition to demonstrating that lamotrigine was effective in two strains of NF1 mice, Anastasaki and Gutmann also demonstrated that the medication was likely safe because it was effective at lower dosages than those used to treat epilepsy. Better yet, they discovered that the medication produced long-lasting benefits when used as a therapy and preventative measure. Tumour-bearing mice, beginning at 12 weeks of age, received treatment for four weeks, during which time the tumours stopped growing and the mice’s retinas exhibited no further damage. Even four months after treatment concluded, mice given a four-week course of the medication beginning at 4 weeks of age, before tumours usually appear, did not exhibit any tumour growth.

Also Read| Reduced risks of common diseases through the inherited predisposition for higher muscle strength

According to these results, Gutmann hypothesises that young children with NF1, perhaps between the ages of 2 and 4, would benefit from a one-year course of therapy to lower their risk of brain tumours.

The idea that we might be able to change the prognosis for these kids by intervening within a short time window is so exciting,

If we could just get them past the age when these tumors typically form, past age 7, they may never need treatment. I’d love it if I never again had to discuss chemotherapy for kids who aren’t even in first grade yet.

David H. Gutmann

Source: Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis News

Journal Reference: Anastasaki, Corina, et al. “NF1 Mutation-driven Neuronal Hyperexcitability Sets a Threshold for Tumorigenesis and Therapeutic Targeting of Murine Optic Glioma.” Neuro-Oncology, https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noae054.