Some extremely toxic elements of snake venom can now be counteracted by new proteins that are not found in nature. The development of these toxin-neutralizing proteins using deep learning and computational techniques raises the possibility of producing safer, more affordable, and more accessible treatments than those that are already on the market.

Over 2 million people are bitten by snakes every year. According to the World Health Organization, 300,000 of them experience serious problems and long-term disability due to limb deformity, amputation, or other aftereffects, and over 100,000 of them pass away. Poisonous snakebites are a major public health hazard in Papua New Guinea, South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America.

Researchers from the Technical University of Denmark and the UW Medicine Institute for Protein Design are spearheading a computational biology initiative to find more effective antivenom treatments.

Their findings were published in the journal Nature.

Susana Vazquez Torres of the UW School of Medicine’s Department of Biochemistry and the UW Graduate Program in Biological Physics is the paper’s principal author. Her hometown of Querétaro, Mexico, is close to habitats for rattlesnakes and vipers. Her career objective is to develop novel medications to treat neglected illnesses and wounds, such as snakebite.

Finding methods to neutralize venom collected from specific elapids was the main focus of her study team, which also included foreign specialists in tropical medicine, medications and diagnostics, and snakebite research from the United Kingdom and Denmark. Cobras and mambas are part of the broad group of poisonous snakes known as elapids, which inhabit the tropics and subtropics.

The majority of elapid species have two tiny, shallow-needle-shaped fangs. Venom can be injected by the fangs from glands at the back of the snake’s mouth during a persistent bite. Three-finger poisons are among the potentially fatal substances found in the venom. These substances cause cell death, which harms body tissues. More gravely, by blocking communication between nerves and muscles, three-finger toxins can induce paralysis and death.

Currently, antibodies extracted from the plasma of animals inoculated against the snake toxin are used to treat venomous snakebites from elapids. The antibodies’ efficacy against three-finger toxins is limited, and their production is expensive. The patient may experience respiratory distress or shock as a result of this medication, among other severe adverse effects.

Efforts to try to develop new drugs have been slow and laborious,

Vazquez Torres

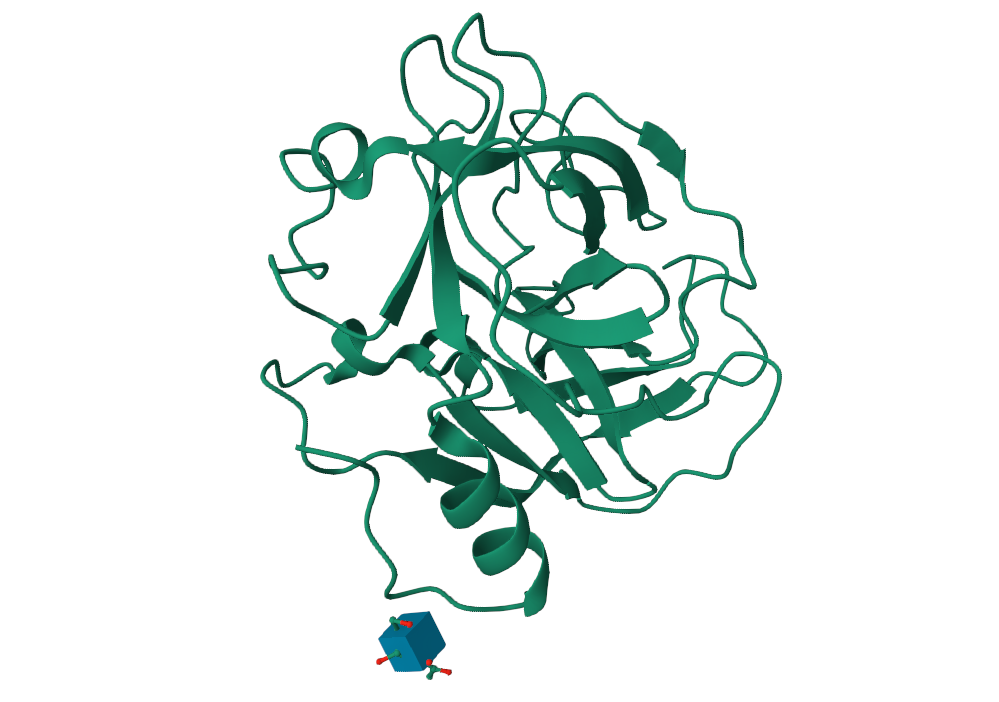

To try to expedite the development of more effective medicines, the researchers employed deep learning computational techniques. They developed novel proteins that bound to the three-finger toxin compounds and disrupted their neurotoxic and cell-destroying effects.

The scientists were able to develop designs that produced proteins with high binding affinity and thermal stability through experimental screening. The deep-learning computer design and the real manufactured proteins nearly matched each other at the atomic level.

The developed proteins successfully neutralized each of the three subfamilies of three-finger toxins that were tested in lab dishes. Mice administered the developed proteins were shielded from a potentially fatal neurotoxic exposure.

Designed proteins offer significant benefits. Instead of using recombinant DNA technology to immunize animals, they might be produced with consistent quality. (In this instance, “recombinant DNA technologies” refers to the laboratory techniques the researchers used to create a novel protein from a computationally created blueprint.

Additionally, compared to antibodies, the new proteins that are made to combat snake toxins are tiny. Their reduced size may enable them to more readily penetrate tissues, hence reducing damage and rapidly counteracting the poisons.

The researchers believe that using computational design methodologies could lead to the development of various antidotes in addition to creating new opportunities for the development of antivenoms. These techniques may also be applied to find drugs for underdiagnosed diseases that afflict nations with a dearth of scientific research funding.

Source: University of Washington School of Medicine – News

Journal Reference: Vázquez Torres, Susana, et al. “De Novo Designed Proteins Neutralize Lethal Snake Venom Toxins.” Nature, 2025, pp. 1-7, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08393-x.

Last Modified: